May 02, 2017

Peter’s Story

by Robbie Shell

I met Peter two years ago when I was volunteering at Inglis House, a residential facility in Philadelphia for people who are wheelchair users and need help taking care of their most basic needs. Peter had multiple sclerosis complicated by a series of strokes that left him severely compromised — confined most of the time to his room, barely able to speak and often in pain from MS-related spasms.

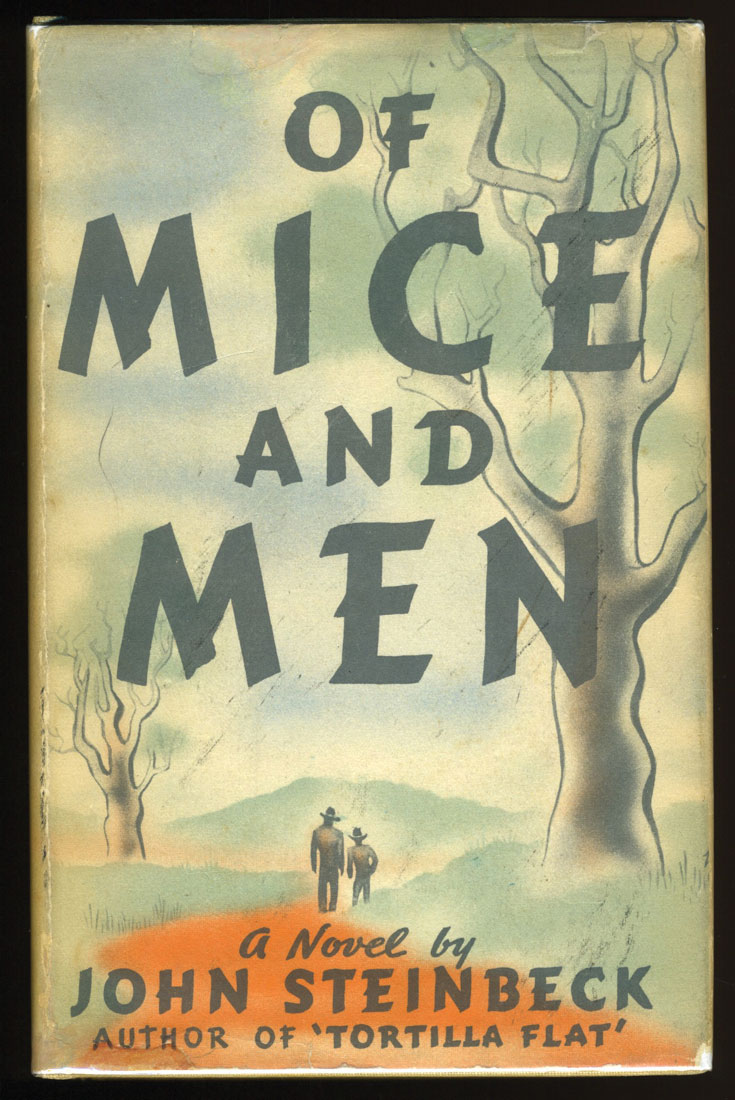

But when he could get up — hoisted into his motorized, self-driven wheelchair by a contraption that lifted him out of bed in a series of graceful loops — he made the most of it. I would follow him down the hall to the large main floor auditorium where I read Of Mice and Men (his choice) in small increments. On warm days, I walked behind him down ramps that led to gardens in the back where he positioned his wheelchair to always face the sun. His condition prevented him from telling me about the life he led before this relentless assault on his independence, but I learned from a plaque on his wall and a newspaper article that he was a most accomplished man.

wall and a newspaper article that he was a most accomplished man.

He had been a delegate at the Democratic National Convention in 1980, an organizer of the first international educational conference on HIV/AIDS for educators in Africa, and a trade union representative for the International Federation of Free Teachers’ Unions in Amsterdam. He was multilingual and taught Spanish and French in high schools at home and abroad. He liked classical music. He had a daughter.

My most vivid memory of Peter was an hour we spent in the garden one autumn afternoon going from booth to booth at a carnival that Inglis had set up for those residents able to participate. Some of the games were manned by volunteers from area high schools, teen-age promoters calling for the crowd to try their hand at throwing a ball into a miniature basketball hoop, tossing a beanbag, popping a balloon.

Peter and I stopped in front of a table where the goal was to knock down empty soda cans stacked in a pyramid. The volunteer, a student at a high school a few miles from Inglis, handed Peter one of the balls. Peter’s left hand was paralyzed, but his good right one wrapped around the ball and threw. With no muscle behind it, the ball dropped in front of the table. Peter moved his wheelchair a few inches forward and tried again. The ball reached the table but not the cans. It was progress, and Peter’s body moved back and forth very slightly — one of the ways he was still able to express emotion.

Peter and I stopped in front of a table where the goal was to knock down empty soda cans stacked in a pyramid. The volunteer, a student at a high school a few miles from Inglis, handed Peter one of the balls. Peter’s left hand was paralyzed, but his good right one wrapped around the ball and threw. With no muscle behind it, the ball dropped in front of the table. Peter moved his wheelchair a few inches forward and tried again. The ball reached the table but not the cans. It was progress, and Peter’s body moved back and forth very slightly — one of the ways he was still able to express emotion.

The volunteer moved the pyramid closer to the table’s edge. Peter reached for the third ball, threw it, and knocked down one of the cans. It was a homerun in the seventh game of the World Series, a touchdown in the closing minutes of the Super Bowl, a goal in the last seconds of the Stanley Cup finals. The volunteer and I erupted in cheers.

Before Peter and I moved on, I turned to the student and asked him if he took French or Spanish at school. Yes, Spanish. I told him that this man in front of him — strapped into a wheelchair, unable to sit up on his own or hold a book or any mobile device — had once been appointed to a presidential commission that traveled the globe advising the heads of high school language programs.

The student high-fived the air above Peter’s head, a reaction that renewed my faith in

high school students everywhere. But it was Peter’s reaction that lit up the day.

He grinned — beamed — so broadly, so spontaneously, that it changed forever how I will remember him. Those few seconds were confirmation of a sensibility, an intellect, an ego, that lay just beneath the surface of his disability, needing only the briefest acknowledgment to break out into that huge, face-splitting smile. He was not a man in a wheelchair, but a man who had connected with thousands of people, young and old, in classrooms and at conferences around the world.

Peter died last year at age 65. For a few seconds, in front of a table full of empty soda cans, I could see the active, engaged person he once was. He could see that person, too.

In some cultures, people don’t become invisible as they age or cope with disability. They are not defined by accident or illness but are respected for what they have done and what they know. Their accomplishments and the wisdom that comes from experience are celebrated by the community around them.

In our society, we are culturally programmed to disregard such people if they can’t keep up. And when, in fact, they can’t — because of what has been described as “bad genes or bad luck,” or simply aging — we tend to leave them behind until they disappear from our view.

Peter had not disappeared. He was present, but “differently” present. One acknowledgement of his earlier life, one show of respect from a high school student, and he emerged from the shadows in full color, vivid and real. Scratch the surface and you saw a former world-class educator, an activist, a man who rocked the world.

Every person has a backstory — the narrative of their lives that brought them up to the present. Sharing someone’s narrative is a way to appreciate the person he or she is now, and perhaps to better understand the challenges that inevitably lie ahead. It may even be a way of enriching ourselves.

When it comes to the disabled or the elderly, these backstories are all the more important because they are connective tissue — keeping these people in the conversation, even if, like Peter, they can no longer speak for themselves.

Author, reporter and lecturer, Robbie Shell is a long-time Inglis volunteer. You can read her recent article in "The Wall Street Journal" - "When Enough Doesn't Have to Mean More" by clicking here.

Author, reporter and lecturer, Robbie Shell is a long-time Inglis volunteer. You can read her recent article in "The Wall Street Journal" - "When Enough Doesn't Have to Mean More" by clicking here.